In 1884, a competition was announced for organist of Park Hall and St. Andrew’s Church in Cardiff, Wales. Lemare, then 19 years old, won the post out of 149 applicants, but he did not stay in the position for long.

Lemare next competed for a position as organist for the Sheffield Parish Church, England, this time against 45 other applicants, and won again. He stated, “The church burgesses didn’t know until later that they had appointed someone under age because my birthday was listed as a year earlier.” (OIHM p. 20)

Lemare played an active role in the church services at Sheffield and held the post for six years. In 1888, he played his Andantino in D Flat for the first time with a thumbed counter-melody and novel registration. The piece “had soul” and was especially well liked by the congregation. It later became a popular song of the era called “Moonlight and Roses”.

From 1894-1897 Lemare held the post of organist at Holy Trinity, Sloane Square, London. He instituted weekly organ recitals, put together a choir of 40 boys and 20 professional singers, and performed such works as Brahms Requim and St. Mathew Passion.

Lemare worked closely at Holy Trinity with the rector, Reverend Robert Eyton, who was a music aficionado. Lemare stated: “I was given carte blanche to engage or discharge any member of the choir. I was asked to improvise for ten or fifteen minutes before each service to inspire Reverend Eyton with a subject for his sermon.” (OIHM p. 22)

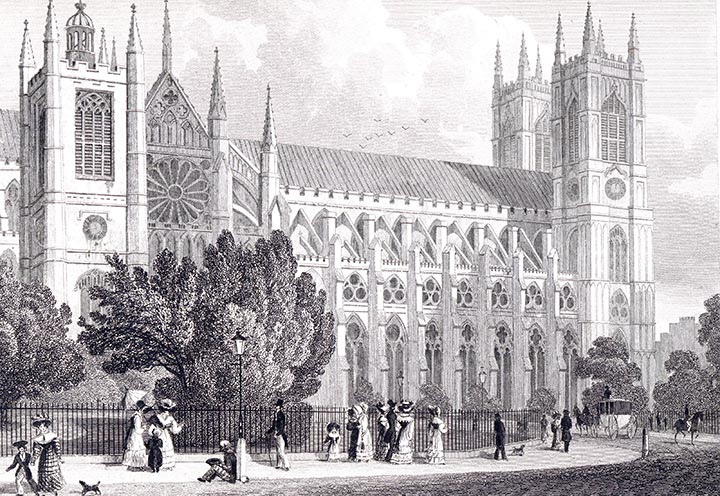

In 1895, the Times announced that Reverend Eyton of Holy Trinity Sloane Square had been appointed Canon of Westminster and Rector of St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster Abbey. Lemare followed Reverend Eyton to St. Margaret’s—taking the whole choir from Holy Trinity with him.

Lemare held the post of organist at St. Margaret’s Westminster, Parish Church of the House of Commons, from 1897-1902. It was a good setting for his Wagnerian orchestral ideas.

Lemare was under contract at the time with Schotts, Wagner’s publishers, to transcribe everything that was possible for the organ. He stated, “The old collegiate school of organists was aghast at these publications and looked upon me with up-raised hands and “holy horror” as a charlatan in their midst.” (OIHM p. 23)

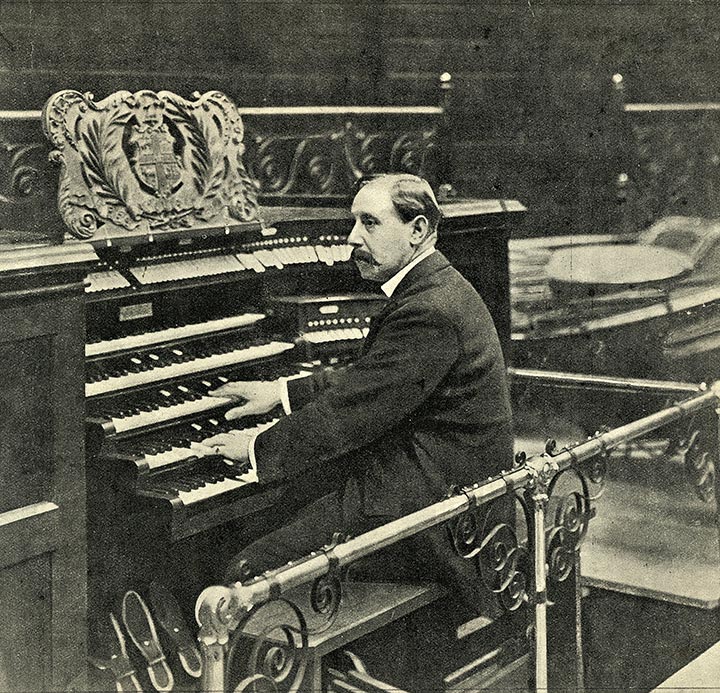

Lemare designed a three manual instrument at St. Margaret’s that was especially for transcription playing. It was built by J.W. Walker & Sons at a cost of 2953 pounds. The instrument was first used in 1897 for the Queen’s Jubilee Thanksgiving Service of the House of Commons. Lemare stated: “I saw to it that the big pedal department contained a specially constructed, large scale open wood 32 ft. Such tones were never heard before in St. Margaret’s or in few other churches of its size.” (OIHM p. 22)

In 1898, Lemare obtained permission from Cosima Wagner to present the first act of Parsifal at St. Margaret’s Church. The newspapers carried at least nineteen reviews of the concert. Felix Mottl, whom Lemare had heard conduct at Bayreuth, was present and said: “I have nothing to say, except beautiful, beautiful.” Lemare stated: “I felt very insignificant in his presence trying to convey an impression of an orchestra on a few more or less expressionless organ pipes.” (OIHM p. 23)

Lemare’s recitals at St. Margaret’s Westminster became a mecca for musicians. He stated: “One never knew who was present in that immense and silent crowd—royal personages, noted composers, authors, conductors, singers, etc. Yet, the organ was alone heard in a darkened church.” (OIHM p. 23)

The Musical Courier pronounced Lemare to be “unquestionably the greatest organist in England.”

Lemare’s life outside of St. Margaret’s Westminster was exploding with activity. He played organ recitals and dedications throughout England, wrote articles, lectured on Wagner, brought out volumes of transcriptions and arrangements and composed five new organ works.

In 1900, Lemare took a leave from St. Margaret’s to make a tour of fifteen recitals in America sponsored by the Austin Organ Company.

In December of 1900, Lemare crossed the Atlantic for the first time on the White Star liner Teutonic to visit his fellow organist, Edward Horsman in New York City. Horsman arranged for Lemare to play a recital on the large double organ in St. Bartholomew’s Church on Fifth Avenue. Upon his arrival, the New York chapter of the American Guild of Organists hosted a dinner in his honor.

At the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, a competition was underway for a new organist to fill the post vacated by the death of Frederic Archer. After Lemare played to a crowd of over 6,000 people at Queen’s Hall, further auditions were cancelled and Lemare was cabled that he was appointed Organist and Director of Music at the Carnegie Institute. His salary was $4,000 a year—five times what he had received at St. Margaret’s Westminster.

London was not happy about the defection of their organist. “America’s gain of one of the most deservedly distinguished organists of his time is a very decided loss to English music.” (London Times, Feb 11, 1902)

The Pittsburgh Post printed a typographical error that stated Lemare had been installed as city organist under the most “suspicious” (instead of “auspicious”) conditions. (Pittsburgh Post March 2, 1902) The Pittsburgh Leader noted that Lemare was an Englishman; “Wasn’t there a law against employing “aliens?” (Pittsburgh Leader, Dec. 24, 1901)

Lemare held the post of organist at the Carnegie Institute from 1902 to 1905. His orchestral transcriptions—by then over a hundred of them—were in demand. His Andantino in D Flat was requested at nearly every concert. Sometimes hundreds of attendees were left outside waiting for seats.

At the 494th concert at the Carnegie Music Hall, ten thousand people nearly disrupted the concert coming and going with a “mighty rush” between selections. The Pittsburgh Post commented that the performer may not have suspected that he had practically a new audience for every number.

Lemare was taking more and more time away from Carnegie Music Hall for touring. He resigned in September of 1904--leaving the Carnegie Committee feeling that Lemare acted more on his own interests than theirs.

In the Spring of 1906, Lemare left for San Francisco and a second Australian tour. Luckily, he stopped to play a concert in Salt Lake City, or he would have arrived in San Francisco on Wednesday April 18, the day of the San Francisco earthquake. As it was, when the train pulled into Oakland the following day, four square miles of San Francisco was in flames. Lemare barely escaped conscription as a firefighter. He promptly embarked from Seattle to Australia where he was to perform at Sydney Town Hall.

When Lemare arrived in Sydney, the organ was in “deplorable” condition. He was appointed to oversee the repair work and chose the firm of W.E. Richardson & Sons. During the next two weeks thousands of pipes were tuned and six assistants repaired the five manuals. Lemare himself supervised the tuning of the full length 64’ reed.

Tonally speaking, Lemare felt that the organ in Sydney was the “largest” in the world. He stated: “Some of our American organs may have considerably more stops, but they cannot compare in volume of tone with the great organ of Sydney.” (OIHM p. 29)

Lemare’s concerts in Sydney got off to a slow start, but after eighteen recitals, the audience was “packed in like a herring barrel” and concerts in Melbourne and Adelaide followed.

The Grand Organ in Melbourne was also in need of repair. The sharps on the pedalboard were worn down almost to the naturals, the touch was heavy, and stops came out “by the yard.” Lemare acted as consultant. He stated: “I was engaged to draw up the specification and supervise the erection of the parts that were made at the firm’s English factory.” (OIHM p. 27)